The Global Proficiency Frameworks for reading and mathematics are taking shape. Developed by the UNESCO Institute of Statistics and USAID, in collaboration with a host of other organisations including the World Bank, the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office and the Gates Foundation, the frameworks make explicit the ‘basic skills’ required of all students globally to thrive in society.

There is much to welcome about such an effort – foundational learning is the precursor of academic and lifelong success. This really is just about ensuring the building blocks of learning are in place.

These documents would not look out of place among the most heralded of national curriculums. Except now the scope is truly global; a common core of clearly stated learning outcomes that all education systems can strive for.

Where measurement goes wrong

Robust measurement is essential to tracking progress towards SDG4, and to highlighting areas in need of further support and investment. The promise of a global framework is that it offers a common yardstick for progress. If we could measure the knowledge and skills of all students according to these benchmarks, we would have a means of comparing the performance of one system to another, and of evaluating policies against outcomes we have all committed to.

But that remains a big if. Measurement is the thorn in the side of policymakers. Only 17 of 48 countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, have end-of-primary assessment data that is accurate or aligned with global standards. And even that data is but a snapshot in time. As the pandemic rages on, learning data that isn’t continually updated risks becoming obsolete in a matter of weeks.

The dilemma we’re faced with is that, with traditional measurement tools, assessment is a major distraction from learning. It’s costly to administer, plagued with reliability issues and almost impossible to keep up-to-date. Perhaps most of all, the resulting data does little to inform teachers’ practice; a key determinant of student learning outcomes.

What automated, real-time assessment enables

But there is a way around this conundrum, and that is to form a tight coupling between learning and assessment. The technologies now available to us make this possible. Virtual tutoring platforms like Maths-Whizz, for example, integrate assessment into every single lesson; learning and measurement are integral to one another. Assessment data emerges as an automatic by-product of learning – there is no separate effort, no additional cost.

As learning data is generated in real time, key insights are shared with whoever needs it: parents can monitor their children’s progress, teachers can plan ahead armed with new insights and system leaders can track their progress according to national and international benchmarks. We can see, for instance, the disparities between different countries, and between different communities within the same country.

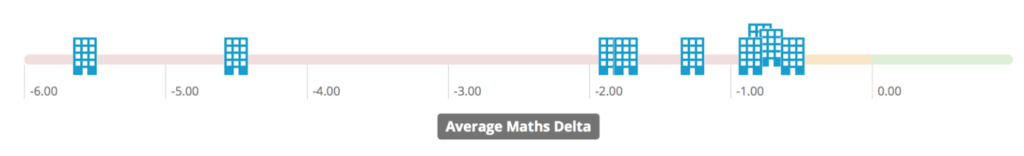

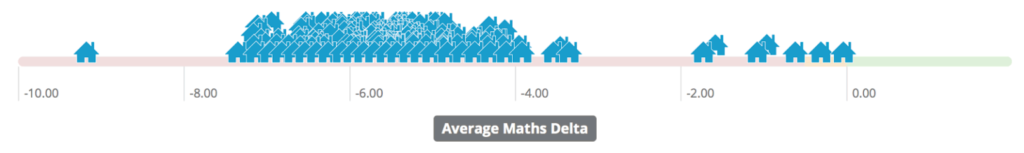

In these comparison charts, each icon represents a major implementation. ‘Maths Delta’ is a quantitative measure of where students are with respect to Whizz’s international benchmark. The first chart maps the Maths Delta of different regions – the leftmost icon represents rural Kenya, where students were shown to be almost six years behind expected levels, and several years behind developed nations. The second chart maps the Maths Delta of schools across Kenya, including a handful of private schools whose average Delta is in line with most other territories, thus highlighting the stark disparities in learning between marginalised and non-marginalised communities in Kenya.

Since this data is updated in real time, it enables key stakeholders – from teachers to programme managers to policymakers – to take course-corrective action as they evaluate what is and isn’t working on the ground.

And since assessment is continuous and fine-grained, we can measure progress against a full scope of specified outcomes. The Global Proficiency Framework contains hundreds of descriptors, each pertaining to a bite-sized learning outcome. No single assessment can possibly capture the full range of what such frameworks stipulate students should know. But with students assessed thousands of times over as an in-built part of their learning, digitised forms of assessment offer complete coverage – there’s no need for subsampling or other corner-cutting mechanisms.

It would be highly impractical (and a touch too convenient for any EdTech provider) to suggest every student needs to be on the same learning platform for these comparisons to hold. But this isn’t the case. We can lean on the same thinking that undergirds the Global Proficiency Frameworks to require only that whatever assessment tools a given system adopts, its question banks are demonstrably aligned and explicitly mapped to those core learning outcomes.

It is even misguided to suggest that the scope and sequence of learning material must be consistent across systems. We have developed robust technical methods to evaluate students’ learning (in terms of a Maths Age) even when the ordering of topics and learning objectives vary from one system to the next.

There’s enormous potential for technology to support the goals of learning and assessment in tandem, without the usual drawbacks concerning cost and accuracy.

Measurement need not be a distraction from the things we care about as educators.